G. A. Chandru - An Indian's History in Yokohama

An Indian’s History in Yokohama, Japan.

“The family I come from believes in the Hindu faith, and has its roots in the Sindh province, in what is now part of Pakistan…. Under British rule, the people of Sindh were encouraged to travel … and act as … go-betweens between various cultures, in particular in areas of trade and finance.

Under these circumstances, my father was sent to Yokohama in 1917. He worked for my grandfather’s company Tarachand Parsram, and was sent to run the Japan branch which was located in Yokohama.”

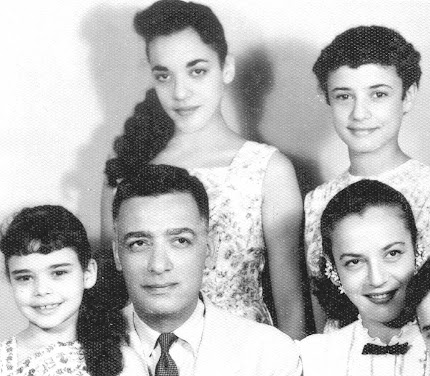

G. A. Chandru relates the circumstances which led to the beginning of his family’s long history in Japan. An Indian resident whose personal history in Yokohama spans over 50 years, Chandru, the President of Nephews International, energetically details his family’s history as Indians in Yokohama.

Chandru’s father had moved to Yokohama in 1917 to manage a branch of his father’s business. However, after only three years he returned to India to aid in its struggle for independence from Britain. Thus, Chandru, who was born in 1924 in Sindh, never once laid eyes on Yokohama during his youth. Even so, during his childhood he held a great interest in Japan. “I recall how [my father] talked about the very high social and cultural standards of Japan. Whenever someone came back from Japan we received ‘Tombow’ pencils, fancy toys, and were shown the Japanese cameras. This created in our mind a very special admiration of Japan, of the beautiful designs and perfect performance in the products we saw.”

Chandru’s father came to and left Japan during a period when Indian trade of silk, cotton, and yarn was thriving; Indian traders had been active in Japan since the late 1800s.

Memorial fountain in Yamashita Park for the Indians who perished in the Great Kanto Earthquake

However, the prospering Yokohama silk and textile trade would soon be thrown into crisis by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. The earthquake, of magnitude 7.9, left Yokohama in ruins, and in the earthquake’s aftermath, large numbers of Indians relocated to Kobe with the aid of the Kobe city and national governments. However, a number of Indians later returned to Yokohama, and it is said that just before WWII, India was Japan’s third-largest trading partner, after the U.S. and China.

Merchants traded on slim profit-margins, turning profits only by moving large quantities of goods. They sold silk at-cost, earning money only on the sale of the wooden packing cases (petti) holding the silk, constructed from high-quality kiri wood.

However, the unfolding of WWII shook the Indian community and many left Japan, preferring that to the alternative of being interned in Japanese camps as British subjects.

After the end of the war in 1947, India’s newly-won independence from British rule triggered a religious conflict which tore the country into two: Pakistan, an Islamic state, and India, a secular state.

Chandru’s family became subject to intense religious persecution in Pakistani Sindh, and was forced to abandon everything and take refuge in India. There, Chandru became responsible for supporting his parents and siblings, and he remembers this period as the saddest in his life. However, the images of Japan were engraved in Chandru’s imagination, and in 1953 he sprang on an opportunity to try his luck in business in Japan. “I sensed a bright future [in Japan], a chance to work hard and have my hard work rewarded."

When Chandru arrived in 1953, though Yokohama was still rebuilding, Indian businesses had already planted firm roots. Chandru, who initially worked as the manager of an Indian trading firm located in Yamashita-cho, recalls his early years in Yokohama. “I worked hard day and night for 6 years…. in my 7th year, I started my own firm…. I called the company Nephew’s International, taking the name from the company which my Uncle has started with his nephews (myself included) in India during the British rule.”

Textiles and fabrics, mainly silk, remained significant exports through the 1950s; however, they were later surpassed in popularity by synthetic textiles such as nylon. By the 1960s textiles had become less profitable, and the trade of electronics, technology goods and sundries became more common. However, in general, as Japanese industries expanded their global networks, the need for the middleman was eliminated, and slowly Indian businesses either moved abroad or west to Kobe and Osaka.

Thus by the 1980s, trading in Yokohama had slowed, and many Indians sold their properties in Yamashita-cho or converted them to apartment buildings and parking lots. Some moved to Kobe or Osaka, and others returned to India. Currently there are only a small number of “old-comer” Indian residents in Yokohama remaining; however, there has been a recent influx of Indians coming from the IT hubs of India (Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai) to work in software companies in Yokohama, as well as those who come through their work in multinational finance or engineering companies.

Darren Yamaguchi

________________________________________

Mr. G. A. Chandru is a family friend since 40 years.

An Indian’s History in Yokohama, Japan.

“The family I come from believes in the Hindu faith, and has its roots in the Sindh province, in what is now part of Pakistan…. Under British rule, the people of Sindh were encouraged to travel … and act as … go-betweens between various cultures, in particular in areas of trade and finance.

Under these circumstances, my father was sent to Yokohama in 1917. He worked for my grandfather’s company Tarachand Parsram, and was sent to run the Japan branch which was located in Yokohama.”

G. A. Chandru relates the circumstances which led to the beginning of his family’s long history in Japan. An Indian resident whose personal history in Yokohama spans over 50 years, Chandru, the President of Nephews International, energetically details his family’s history as Indians in Yokohama.

Chandru’s father had moved to Yokohama in 1917 to manage a branch of his father’s business. However, after only three years he returned to India to aid in its struggle for independence from Britain. Thus, Chandru, who was born in 1924 in Sindh, never once laid eyes on Yokohama during his youth. Even so, during his childhood he held a great interest in Japan. “I recall how [my father] talked about the very high social and cultural standards of Japan. Whenever someone came back from Japan we received ‘Tombow’ pencils, fancy toys, and were shown the Japanese cameras. This created in our mind a very special admiration of Japan, of the beautiful designs and perfect performance in the products we saw.”

Chandru’s father came to and left Japan during a period when Indian trade of silk, cotton, and yarn was thriving; Indian traders had been active in Japan since the late 1800s.

Memorial fountain in Yamashita Park for the Indians who perished in the Great Kanto Earthquake

However, the prospering Yokohama silk and textile trade would soon be thrown into crisis by the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. The earthquake, of magnitude 7.9, left Yokohama in ruins, and in the earthquake’s aftermath, large numbers of Indians relocated to Kobe with the aid of the Kobe city and national governments. However, a number of Indians later returned to Yokohama, and it is said that just before WWII, India was Japan’s third-largest trading partner, after the U.S. and China.

Merchants traded on slim profit-margins, turning profits only by moving large quantities of goods. They sold silk at-cost, earning money only on the sale of the wooden packing cases (petti) holding the silk, constructed from high-quality kiri wood.

However, the unfolding of WWII shook the Indian community and many left Japan, preferring that to the alternative of being interned in Japanese camps as British subjects.

After the end of the war in 1947, India’s newly-won independence from British rule triggered a religious conflict which tore the country into two: Pakistan, an Islamic state, and India, a secular state.

Chandru’s family became subject to intense religious persecution in Pakistani Sindh, and was forced to abandon everything and take refuge in India. There, Chandru became responsible for supporting his parents and siblings, and he remembers this period as the saddest in his life. However, the images of Japan were engraved in Chandru’s imagination, and in 1953 he sprang on an opportunity to try his luck in business in Japan. “I sensed a bright future [in Japan], a chance to work hard and have my hard work rewarded."

When Chandru arrived in 1953, though Yokohama was still rebuilding, Indian businesses had already planted firm roots. Chandru, who initially worked as the manager of an Indian trading firm located in Yamashita-cho, recalls his early years in Yokohama. “I worked hard day and night for 6 years…. in my 7th year, I started my own firm…. I called the company Nephew’s International, taking the name from the company which my Uncle has started with his nephews (myself included) in India during the British rule.”

Textiles and fabrics, mainly silk, remained significant exports through the 1950s; however, they were later surpassed in popularity by synthetic textiles such as nylon. By the 1960s textiles had become less profitable, and the trade of electronics, technology goods and sundries became more common. However, in general, as Japanese industries expanded their global networks, the need for the middleman was eliminated, and slowly Indian businesses either moved abroad or west to Kobe and Osaka.

Thus by the 1980s, trading in Yokohama had slowed, and many Indians sold their properties in Yamashita-cho or converted them to apartment buildings and parking lots. Some moved to Kobe or Osaka, and others returned to India. Currently there are only a small number of “old-comer” Indian residents in Yokohama remaining; however, there has been a recent influx of Indians coming from the IT hubs of India (Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Chennai) to work in software companies in Yokohama, as well as those who come through their work in multinational finance or engineering companies.

Darren Yamaguchi

________________________________________

Mr. G. A. Chandru is a family friend since 40 years.

+Nassef.jpg)

.jpg)